Anal fistula and Anorectal Sepsis (perianal abscess)

Anorectal sepsis is common with over 10,000 admissions per year in the UK. This usually presents with either an abscess in the region of the anus, or a chronic anal fistula.

Acute perianal abscess

It is thought anorectal sepsis originates from the anal glands. These glands are located on the dentate line (the junction between the rectum and anus), and they become blocked with debris which in turn leads to bacterial overgrowth and formation of an abscess (cryptoglandular theory). More rarely Crohn’s disease or other condition leads to the abscess.

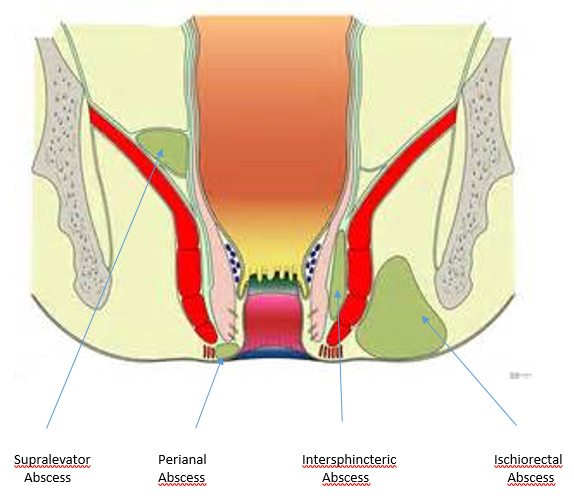

From this point the pus then tracks and spreads along potential planes and spaces, and the type of abscess that forms is dependent on its anatomy and relation to the sphincter complex of the anus.

The most common type is a perianal abscess (60% of cases). The abscess sits underneath the skin of the anal canal and infection does not pass through the external sphincter.

If the track of infection passes through the external sphincter an abscess forms in the space adjacent to the anus and is termed an ischiorectal abscess. This occurs in approximately 20% of cases, and on occasion the infection creates a horse shoe shape around the anus, the so called “horse shoe abscess”.

Intersphincteric abscesses are the third most common, this is when the infection sits between the 2 muscles layers of the anus, the internal and external anal sphincter.

The rarest is the supralavator abscess. In this situation the abscess is located above the levator ani, and is the result of infection tracking upwards from the anus, or sometimes infection from the inside of abdomen (appendicitis, diverticulitis as examples) tracking outwards.

Symptoms and treatment of anorectal sepsis

An acute abscess usually presents with a tender red swelling near the anus. It is usually very painful and sometimes is associated with fevers and a general feeling of malaise.

Whilst on occasion antibiotics can be used to treat the infection, the majority will require incision and drainage, which is a short operation under a general anaesthetic. The abscess cavity is opened, the pus is drained, and the abscess cavity is dressed or sometimes packed. Post operatively the cavity will slowly heal by second intention (slowly fill with scar tissue), a process that takes several weeks and may require community nursing input. The majority will heal and not require any further treatment. However a minority of anorectal abscesses will not heal fully and lead to a diagnosis of an anal fistula.

Anal Fistula (fistula in ano)

An anal fistula is an abnormal connection between the lining inside of the anus and the skin outside the anus. It is formed of a tract (tunnel) which is termed the primary tract. Sometimes there are secondary extensions or tracts branching off this.

Symptoms of an anal fistula

A patient with a fistula in ano often will suffer from recurrent perianal abscesses, accompanied by pain, tenderness, discomfort and a discharge of blood or pus. The symptoms reduce or subside when the abscess bursts or discharges but usually reappears. Sometimes the discharge increases for a few days before settling again.

On occasion patients present with a recurrent abscess once the previous abscess has healed, and requires further incision and drainage.

There may be skin changes as a result of persistent discharge leading to redness and itching.

How is an anal fistula diagnosed?

A full history and examination including proctoscopy and sigmoidoscopy (usually flexible sigmoidoscopy) is required by a specialist colorectal surgeon. Examination under anaesthetic (EUA) complements the physical examination of the awake patient.

Careful examination of a fistula under anaesthetic is the most important aspect of assessment. However previous abscesses, previous surgery and scarring can make clinical assessment difficult. In these circumstances imaging is required, and this is usually an MRI scan of the rectum and pelvis.

In addition an MRI may be required following an EUA, when clinically the fistula is complex, such as with branching tracts or suspicion of undrained collections of pus that are not clinically evident at the time of surgery.

All recurrent fistula in ano should have an MRI pre-operatively to help plan surgery.

Sometimes if there is suspicion that there is another pathology that is causing the fistula further tests may also be required. For example if Crohn’s disease is suspected a stool test for faecal calprotectin often with a colonoscopy or small bowel MRI is needed.

The essential points that must be identified during the assessment (from Goodsall & Miles) include:

- Location of the internal opening

- Location of the external opening

- Course of the primary tract

- Presence of secondary tracts or extensions

- Presence of other diseases complicating the fistula.

Treatment of an anal fistula

Treatment of an anal fistula should be by a specialist consultant colorectal (bowel) surgeon.

The key principles of fistula surgery:

- Early drainage of acute sepsis

- When in doubt or with more complex cases acute sepsis should have adequate long term drainage leaving well established tracts, usually achieved by placing a drainage seton (suture or plastic stitch through the fistula tract)

- Secondary tracts should be drained and / or laid open

- The primary tract is treated depending on anatomical considerations; long term continence and function is the most important consideration.

Treatment options

Fistulotomy

A fistulotomy, also called “laying open of an anal fistula” is restricted to situations where a significant degree of incontinence would not result.

However the majority of anal fistula are suitable to be treated in this way. The surgery involves the fistula tract being opened along its length. This is then left open to heal by second intention (slowly heal with scar tissue) which usually takes a few weeks to fully heal. The surgery is usually performed under a short general anaesthetic and is usually a day case procedure.

Setons

Sometimes an anal fistula is not suitable to be laid open immediately. This is because either:

- there is too much sphincter muscle involved, and if cut could potentially risk faecal incontinence

- there are multiple tracts

- there is significant inflammation which sometimes is best drained before definitive surgery

- the exact position of tract related to the external sphincter is unclear at surgery, as a result of scarring or relaxation under general anaesthesia which needs further assessment when the patient is awake and with the tract defined by the seton

In these situations a seton is placed. This is when a thin suture or a fine plastic string (silastic seton) is placed through the fistula tract.

If a seton is placed further surgery is usually required, sometimes to lay open the tract, sometimes to shorten the fistula (staged fistulotomy) and sometimes to change a seton from a silastic (plastic) seton to a thinner suture seton, that will slowly work its way out. This will be discussed with you in detail in the outpatient clinic preoperatively.

Other Anal Fistula Treatment Options

Complex anal fistula are often best treated by a long term seton. However there are several other treatment options available for high fistulae that traverse the sphincter complex. The suitability of each along with the risks and benefits and potential chances of success will be discussed with you in the outpatient clinic.

Biological agents

“Fibrin Glue” is a technique which involves injected a special glue into the fistula. This helps seal the fistula and encourages it to heal.

“Biosynthetic plug” or fistula plug is a biological plug that is inserted into the fistula tract.

Ligation of Inter-sphincteric Fistula Tract (LIFT procedure) is a procedure in which an incision is made in the skin next next to the fistula, the space between the internal and external sphincter is opened and the fistula tract is divided and ligated.

Advancement Flaps involve excising the internal opening of the tract from lining of the bowel, coring out the tract from the bowel wall and placing a flap of tissue into the defect to close it, which is sutured in place.

All of these methods have varying degrees of success reported in the medical literature.

Risks of surgery

As with any operation complications can occur. Fistula surgery is low risk and is usually performed as a day case procedure under a short general anaesthetic.

The main risks are:

Infection

This is rare when a fistula is laid open or when a seton is placed. However on occasion a second fistula tract may be present and not identified at the time of surgery, and a further abscess forms. Antibiotics are sometimes required and further surgery is very occasionally needed. Infection and recurrent abscesses are much common with procedures such fibrin glue, collagen plug, LIFT or advancement flaps.

Faecal incontinence

Incontinence ranges from being unable to control flatus (wind) through to complete incontinence of flatus and stool. Incontinence is rare and every effort is made to prevent it. The level of risk depends on where the fistula is located and the procedure planned. This specific risk will be discussed with you in the outpatient clinic prior to surgery.

Fistula Recurrence

There is possibility that the fistula recurs despite surgery. If this occurs an MRI scan is usually required to plan further surgery and other diagnoses such as Crohn’s disease may be present.

General risks of surgery and anaesthesia

Modern anaesthetics are very safe. Most people are not affected. Rarely some patients develop a reaction to the anaesthetic, or develop a blood clot in the leg (deep vein thrombosis) that can go to the lung (pulmonary embolism). Patients at risk of this are given compression stockings (TEDS) to wear. Very rarely patients may suffer a heart attack or a stroke as result of anaesthesia and surgery.

After your operation

Following discharge from hospital you will be given painkiller medication, and sometimes antibiotics and laxatives. Take these as prescribed. You can shower and bath immediately. Spare dressings and instructions will be provided on discharge.

There are no restrictions on diet following surgery. However it’s advised, for the first 3-5 days to eat relatively light and bland food, and avoid fizzy drinks.

After surgery it is best to walk and mobilise gently, and gradually build up to normal activity as you feel able. You should avoid heavy lifting for the first 2 weeks following surgery.

You should be able to drive after about 3 days. However if you are taking strong painkillers sometimes these affect your ability to drive. If in doubt seek medical advice prior to driving.

Going back to work depends on your job. Most patients are able to return to work by about 1-2 weeks. Specific advice to you will be made on discharge following your operation.

Complications after discharge are unusual. After private surgery we will phone you the following day and you will be given emergency contact details, which you should call if you think something may be wrong.