Haemorrhoids (piles)

Haemorrhoids, often known as “piles” derive from the vascular cushions which sit just inside the anal canal. These anal cushions help with anal sphincter function, aiding in fine control over flatus (wind) and stool. Typically there are three main cushions in the anal canal.

Everybody has haemorrhoidal cushions. The term haemorrhoids or “piles” is usually when problems occur such as bleeding, prolapse (protrude out) or pain.

Why do “piles” develop?

The anal cushions are normally held in place within the anal canal by elastic and smooth muscle fibres. These fibres are called the muscle of Treitz. When these supporting fibres are damaged the haemorrhoid cushions can excessively swell which results in bleeding or prolapse.

This usually occurs as a result of constipation, associated with straining at stool. Pregnancy and childbirth is associated with a higher risk of haemorrhoids. However “piles” can also occur when there are no obvious identifiable risk factors probably as a result of faulty valves within the haemorrhoidal plexus.

Occasionally “piles” occurs as a result of excess back pressure into the anal veins such as portal hypertension (high pressure within the veins of the liver) or raised pressure within the abdomen.

Types of “piles”

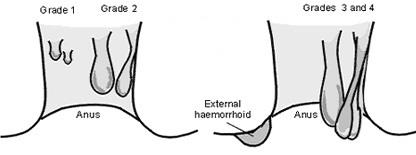

Piles are graded according to degree of severity:

- First degree (grade 1) piles: No prolapse but prominent cushions present.

- Second degree (grade 2) piles: Prolapse of haemorrhoids, but spontaneously reduces (goes back up inside by themselves).

- Third degree (grade 3): Prolapse of haemorrhoids, but requires manual pressure to push them back up inside

- Fourth degree (grade 4): Prolapse of haemorrhoids that is unable to be reduced.

Symptoms of “piles”

Haemorrhoid symptoms are often mild. Internal “piles” often cause episodes of bleeding and in between times sometimes don’t cause any symptoms at all.

When more severe the symptoms includes:

Rectal bleeding

Bleeding from the back passage is the commonest symptom. Often the bleeding is fresh (bright blood) and mainly noticed on the toilet paper after wiping. Sometimes blood drips from the anus, and occasionally blood is noticed in the toilet pain. Usually if this occurs the blood is separate from the stool.

Prolapse

Sometimes “piles” prolapse. This means that on straining, or defecation, the pile protrudes out of the anus. Most of the time this will go back up inside by itself, although on occasion needs to be pushed back by manual pressure.

Feeling a lump

Often patients complain about feeling a lump at the anus, and refer to this as “piles”. Rarely the lump is caused by prolapsed haemorrhoids. More likely the lump is an anal skin tag. Anal skin tags usually grow in response to other pathology, haemorrhoids being one of the causes.

Pain

“Piles” often cause discomfort at the bottom, but are rarely painful. If you have significant anal pain there is often another cause, an anal fissure being most common. On occasion a painful lump develops acutely at the anus. This is usually a perianal haematoma, and is unrelated to “piles”. However in the past it has often called thrombosed external haemorrhoids.

Itching (pruritis ani)

There are potentially many causes of an itchy bottom including anal and dermatological (skin) conditions. Sometimes pruritis ani is caused by low grade faecal incontinence, when a small amount of mucous or a staining of stool leaks from the anus. When this occurs the cause is often due to a prolapsing haemorrhoid.

Are tests (investigations) needed?

Piles themselves, whilst bothersome and often require treatment, are not usually dangerous.

However bleeding from the back passage (rectal bleeding) or feeling of a lump needs further assessment to exclude serious conditions such as rectal or anal cancer.

The tests involve an examination of the back passage with a finger (rectal examination), often with a proctoscopy (small short camera inserted into the anus in the outpatient clinic) and then usually a “flexible sigmoidoscopy” or “colonoscopy”. Sometimes a CT pneumocolon or CTC is used instead.

The majority of the time rectal bleeding is caused by “piles”. However as bleeding from the bottom or a lump is a symptom of bowel cancer tests are usually done to exclude these conditions.

Treatment of haemorrhoids

Most of the time no further intervention is required. Dietary and lifestyle measures such as increased fibre intake, drinking plenty of water each day and avoiding straining at stool is usually enough to reduce symptoms. Sometimes gentle laxatives can help reduce straining if dietary measures do not work.

If simple measure do not work sometimes intervention is then required.

Rubber band ligation

Rubber bands are placed at the apex of the haemorrhoid. This can be done in the outpatient clinic. This causes the “piles” to shrink and as the wound fibroses it becomes fixed to the lining of the rectum, reducing prolapse and preventing engorgement of the anal cushions. Most of the time this is painless, although sometimes there is discomfort at the anus. Bleeding can occur at about day 5 following “banding” and this is seen in about 2-5% of patients. Unfortunately banding isn’t always successful and recurrence rates of up to 40% have been reported.

Haemorrhoid Ligation & plication of haemorrhoidal prolapse

This is an operation that requires general anaesthetic. A suture (or stitch) is placed inside the rectum, above the haemorrhoid cushion. This usually results in the haemorrhoid shrinking as its blood supply is reduced. If there is prolapse this is usually “pleated” up inside the anus.

This procedure has different names, depending on the system used; HALO RAR – Haemorrhoidal Artery Ligation Operation with Recto-anal Repair) (CJ Medical), THD – Transanal Haemorrhoidal Dearterialisation (THD UK Ltd).

Haemorrhoid ligation procedures are effective for treating “piles”. There is a risk of recurrent symptoms in up to 20% of patients. However the procedure can be repeated if necessary and other procedures such as haemorrhoidectomy (see below) could still be performed in the future.

Radiofrequency Ablation

Radiofrequency ablation is a novel technique that involves insertion of a special probe into the haemorrhoidal cushion and high frequency electricity is applied which shrinks the haemhorroid by heating the tissue. It is known as “The Rafaelo Procedure”.

The Rafaelo procedure is a minimally invasive day case procedure. It is often carried out under local anaesthetic, but sometimes sedation or general anaesthetic is used. Most patients report very little pain or discomfort and post operative recovery time is very short.

The Rafaelo procedure is a novel treatment, which means that there is not much evidence about how well it works in the long term, or how safe it is. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) has approved the procedure when it is carried out with special arrangements for clinical governance, consent and audit or research (NICE interventional procedures guidance IPG589). Consequently every patient having the procedure in the UK is entered into an audit registry. You will be invited to complete a quality of life survey before and after the procedure.

Your consultant will discuss the benefits and risks of The Rafaelo Procedure during your initial consultation.

Haemorrhoidectomy

Under general anaesthetic the haemorrhoids are removed. This is a simple day case procedure. Haemorrhoidectomy is a very effective treatment for “piles”, and although in the short term is associated with significant pain, in the long term results and quality of life have been proved to be higher than other haemorrhoid operations.

Risks of surgery

Haemorrhoid surgery is low risk and is usually performed as a day case procedure under a short general anaesthetic. Although rare, complications can occur. There is a small risk that patients may not be able to pass urine following surgery, if this occurs a catheter is usually required.

Pain

Following haemorrhoid ligation surgery patients will often feel discomfort at the anus. On occasion there is severe pain although this is uncommon with this type of surgery. Haemorrhoidectomy, however is associated with significant pain and discomfort afterwards. This lasts for up to 7 to 10 days and often leads to a reluctance to defecate, which in turn leads to constipation. Post operatively patients will be given 5 days of metronidazole (an antibiotic) which has been shown to reduce pain and usually fybogel (a fibre based laxative).

Infection

Surprisingly, given the immediate proximity to faeces, the infection risk is very low. Following haemorrhoidectomy antibiotics are routinely prescribed. However this is for pain and not infection.

Bleeding

Bleeding following surgery is rare but does occur in about 1-3% of patients. This can occur the evening following surgery, but more commonly is a secondary bleed at about 5-7 days post-operatively.

Usually no further treatment is required. Sometimes further hospital admission is required and extremely rarely further surgery is needed.

General risks of surgery and anaesthesia

Modern anaesthetics are very safe. Most people are not affected. Rarely some patients develop a reaction to the anaesthetic, or develop a blood clot in the leg (deep vein thrombosis) that can go to the lung (pulmonary embolism). Patients at risk of this are given compression stockings (TEDS) to wear. Very rarely patients may suffer a heart attack or a stroke as result of anaesthesia and surgery.

After your operation

Following discharge from hospital you will be given painkiller medication, and sometimes antibiotics and laxatives. Take these as prescribed. You can shower and bath immediately. Spare dressings and instructions will be provided on discharge.

There are no restrictions on diet following surgery. However it’s advised, for the first 3-5 days to eat relatively light and bland food, and avoid fizzy drinks.

After surgery it is best to walk and mobilise gently, and gradually build up to normal activity as you feel able and pain allows. You should avoid heavy lifting for the first 2 weeks following surgery.

You should be able to drive after about 3 days. However if you are taking strong painkillers sometimes these affect your ability to drive. If in doubt seek medical advice prior to driving.

Going back to work depends on your job. Most patients are able to return to work by about 1-2 weeks.

Complications after discharge are unusual. After private surgery we will phone you on a daily basis for the first few days. You will be given emergency contact details, which you should call if you think something may be wrong.